Creative Thinking

What is Creative Thinking and Why It Matters

Over many centuries new subjects are added to the school curriculum as the world changes. Sometimes new additions arise from the birth of new disciplines like geography, psychology or information and communications technology, sometimes as result of the demands of employment such as business studies or engineering. And of course, in addition to what appears on the formal curriculum, schools have always had a role in developing the character of their pupils, helping them to distinguish between right and wrong.

In the last thirty years it has become clear that, to thrive in an increasingly complex world, young people need ‘something else’ as well as the knowledge and skills traditionally learned at school.

Some call this something else ‘twenty-first century skills’. But that seems rather imprecise. It also implies that we can forecast what will be needed in seventy year, an unlikely scenario!

Increasingly the ‘something else’ is described as dispositions or competences or capabilities depending where you are in the world. These dispositions include collaboration, communication, critical thinking and creativity. GIoCT, like PISA, believes that of these Creative Thinking, an amalgam of creativity and critical thinking, is particularly important.

Creativity

Over the last seventy years, creativity has become an established field of study starting with the pioneering work of J P Guilford in the middle of the last century. Guilford saw the creative act as having four stages – preparation, incubation, illumination and verification. He suggested that there are two kinds of thinking – convergent (coming up with one good idea) and divergent (generating multiple solutions). Divergent thinking, he argued, is at the heart of creativity. He sub-divided divergent thinking into three components – fluency (quickly finding multiple solutions to a problem), flexibility (simultaneously considering a variety of alternatives) and originality (selecting ideas that differ from those of other people).

Creativity in schools

But while there has been a growing understanding of creativity in the wider world, schools have found it more difficult to see how they can teach it in curricula which are organised around individual subjects. At the end of the last century the National Advisory Committee on Creative and Cultural Education (NACCCE) published a landmark report in the UK on the value of creativity in schools. Also known as the Robinson Report after its chair, the late Sir Ken Robinson, NACCCE argued that a national strategy for creative and cultural education was essential to the process of providing a motivating education fostering the different talents of all children. NACCCE defined creativity as:

Imaginative activity fashioned so as to produce outcomes that are both original and of value.

In 2001, creativity researcher Anna Craft made the simple but important suggestion that there are two different kinds of creativity. There is, she argued, a difference between being a creative genius (big c) and an ordinary person who is creative (little c). She reminded teachers that, in schools, we focus on little c creativity. Craft’s ideas have subsequently been developed by James Kaufmann and Ron Beghetto into their 4C model – mini, little, pro (professional) and big.

In 2012 the Centre for Real-World Learning (CRL) at the University of Winchester was commissioned by Creativity, Culture and Education to develop a model of creativity which could be used in schools. The model has five creative habits of mind, each with three creative thinking skills.

In 2012 the Centre for Real-World Learning (CRL) at the University of Winchester was commissioned by Creativity, Culture and Education to develop a model of creativity which could be used in schools. The model has five creative habits of mind, each with three creative thinking skills.CRL’s model was used by the Centre for Educational Research and Innovation (CERI) at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) as the starting point for an eleven country study designed to understand more about how creativity is taught and assessed in schools. This five dimensional model is now used in more than 35 countries across the world, often, as in this example from Rooty Hill High School in Sydney, Australia, developed by schools to show how creative thinking can be integrated with pedagogy and curriculum.

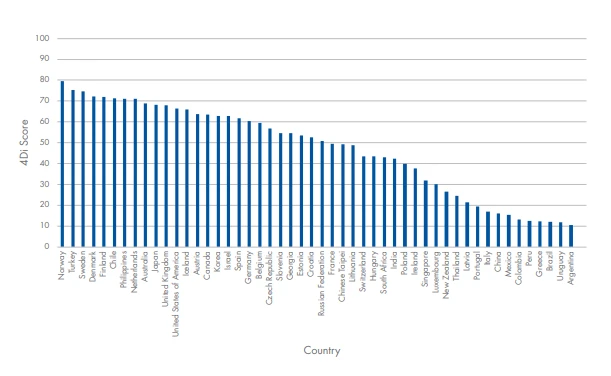

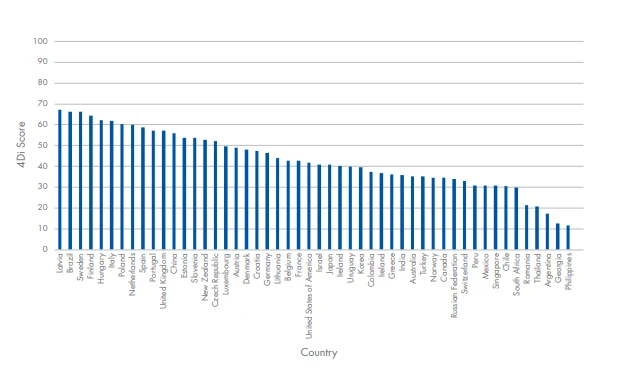

In a landmark report the Centre for Strategic Education CSE and Center for Curriculum Redesign have gone one stage further and developed a way of ranking countries according the degree to which their National Curricula focus on competences like Creative Thinking. The first index below is for Creativity and the second for Critical Thinking. Approximation of any kind of rank order as definitions of Creativity and Critical Thinking vary across the world. So too does the availability of data. Nevertheless, the tables provide interesting food for thought.

A recent study by the OECD exploring the fostering of students’ Creativity and Critical Thinking offers useful guidance as to how Creative Thinking can be taught and assessed. The countries involved in the study were Brazil, Holland, France, Hungary, India, Russia, Slovakia, Spain, Thailand, USA and Wales.

Close up on Australia

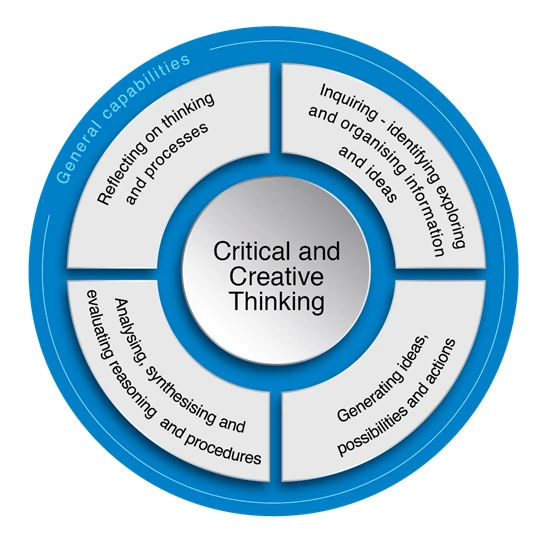

Across the world Australia has led thinking in terms of describing, mandating, embedding and assessing Creative Thinking. Creative Thinking is one a number of general capabilities and is referred to as Critical and Creative Thinking. The Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) provides national guidance:

Each State then interprets this general guidance. In Victoria the Education Department has further simplified the four elements described by ACARA into three – Questions and Possibilities, Reasoning and Meta-Cognition. It also produces detailed guidance for schools showing progression from the beginning of schooling through to High School. Victoria has led the world in assessment, developing scenario-based online activities to assess progress of fifteen year old students in Critical and Creative Thinking.

In Western Australia, in partnership with the Education Department, a community organisation FORM has pioneered the teaching and assessment of Creative Thinking in schools through its Creative Schools programme. A Field Guide produced jointly by FORM and Rethinking Assessment offers practical suggestions for teachers.

Contact us

Interested in learning more? Contact us at

info@gioct.org or fill in the contact us form to discover how to make a submission of your creative thinking project.

Sign up for GIoCT's monthly newsletter

Join the Movement

Always stay updated with the latest developments and events on creative thinking with our monthly Creativity Snapshots!