Assessing Creativity

Assessment, pedagogy and curriculum are integrally connected. What you teach depends on what is assessed. How you assess depends on what is being taught and how it is being taught. Across the world politicians, employers, researchers, parents and all those who work in schools are waking up to the fact that today’s assessment practices are no longer fit for purpose.

Currently the knowledge that is typically assessed is from a narrow range of subjects, rarely explored in depth and almost never inter-disciplinary. Practical knowledge and skill is not much assessed in general education and individuals rather than groups remain the focus. Complex, higher order skills are rarely assessed in ways that recognise the subtleties involved. Many dispositions or capabilities known to be important in life are not assessed at all. As Sandra Milligan and colleagues put it recently:

Without a focus on mastery of generic capabilities, assessment and teaching practices tend to privilege memorisation, essay writing, individual mastery of set content and solving of problems with formulaic solutions. The risk is that schools create students dependent on direct instruction, cramming, drilling and coaching, reliant on expert instruction by teachers who are expected to guide learners through a carefully prescribed body of knowledge, assessed in predictable ways. (Milligan et al, 2020. p.14)

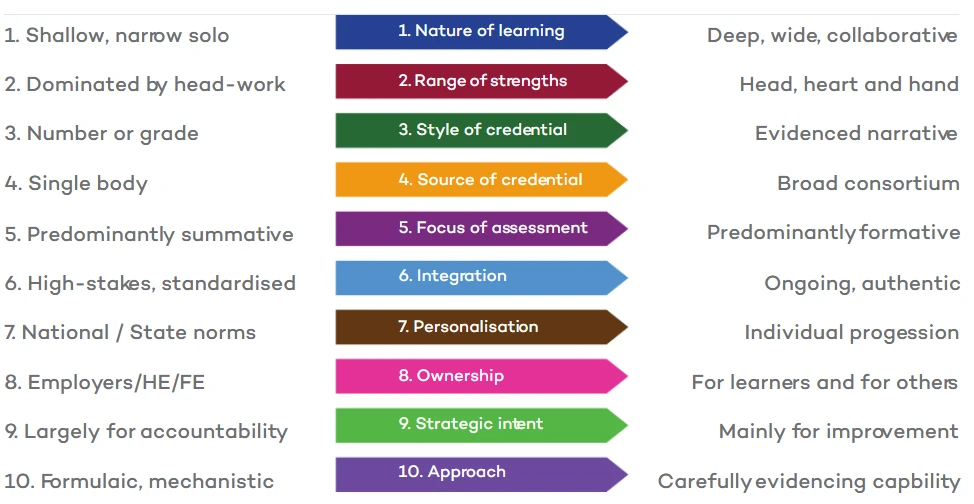

Assessment in schools is changing albeit more slowly. The speed of change is in part due to the difficulty of changing national assessment systems given the need to satisfy employers, universities, colleges and, perhaps most significantly, parents. For parents vote for governments, governments operate in four or five year cycles and changes in national assessment systems are often seen as statements of political belief signalling so-called progressive or traditional views. The figure below summarises some key trends.

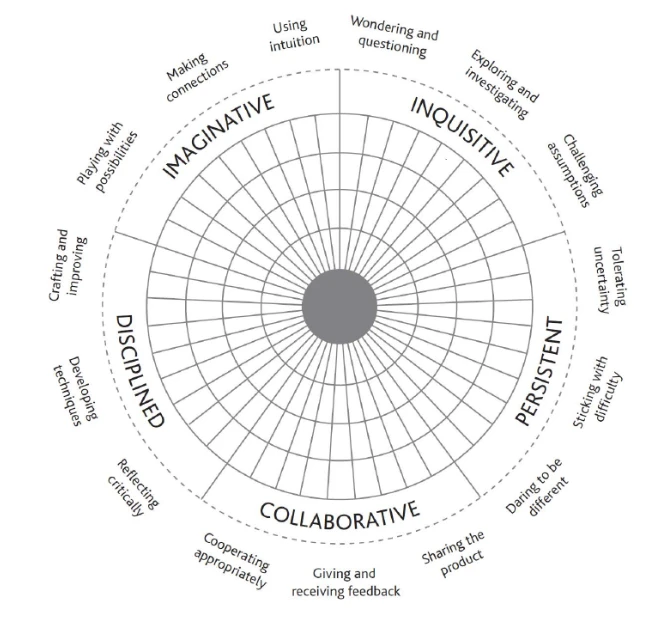

The assessment of creativity goes back some seventy years to psychologist J.P. Guilford who first suggested the value of measuring of creativity (Guilford, 1950). But while researchers in the wider world have developed many well-used ways of measuring creativity – the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking is a good example (Torrance, 1966) – it is only in the last two decades, as national curricula have begun to specify dispositions such as creative thinking, that educators have begun to consider the benefits of assessment. In 2012, with colleagues at the Centre for Real-World Learning (CRL), a five-dimensional model of creativity was developed and illustrated some ways in which the progress of young people’s creativity could be tracked (Lucas et al., 2013), see below:

The CRL five-dimensional model of creativity (Lucas et al., 2013)

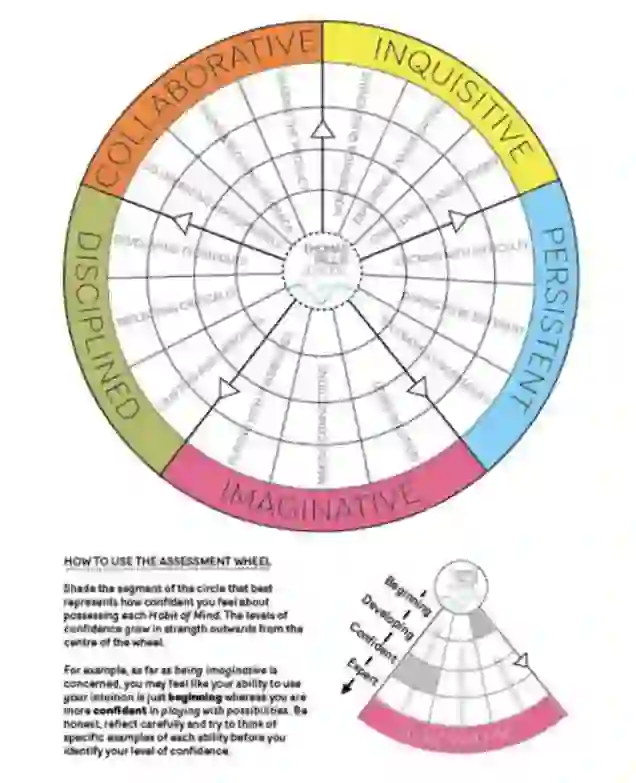

This was then further developed into a trial visualisation tool to allow students to self-assess and chart progress of their development on four levels- beginning, developing, confident, and expert. See below to see how this was adapted:

The Creative Habits of Mind Assessment Wheel

In 2022, the PISA Assessment tested the creativity of 15-year olds, seeksing to clarify not just the elements of creative thinking – generating diverse ideas, generating creative ideas and evaluating and improving ideas – but also to suggest two domains in which they might be embedded and two modes through which they might be expressed, see below:

PISA Creative Thinking Test (OECD, 2019, page 23)

The PISA 2022 Creative Thinking assessment introduces two methodological innovations.For the first time in PISA students will have the chance to produce a visual artefact, rather than construct a written response or choose the correct answer. The assessment also only includes open-ended tasks with no single solution but with multiple correct responses. Rubrics and sample responses from field trials will be used in the assessment process.

This represents a significant step in the inclusion and assessment of creative thinking into the basic curriculum. We look forward to the results of the PISA Creative Thinking Assessment next year.

For more information on the assessment of creative thinking, please read ‘A field guide to assessing creative thinking in schools’, by Bill Lucas, Chair of the Advisory Board at GIoCT. The link to this is here.